Why springtails are the best

Entomobrya intermedia eating pollen grains

Springtails, officially known as Collembola, are a small and incredibly common invertebrate and a big part of the soil mesofauna, worldwide. They’re objectively and categorically way better than horses, tigers, dogs, bush babies, koalas and hedgehogs. In fact, they are better than any other animal I can think of. They are hands down the best animal in the world. Fact.

Despite how great they are, most people still have no idea that they even exist, which is beyond tragic and all the more reason to write this blog post.

Pseudachorutinae, tropics of Australia

Springtails, which play such an important part in soil health and the soil food web, are struggling to survive in this fast changing and rapidly degrading human-dominated world, amidst rapid climate change, politics, pesticide usage, habitat destruction and bad farming, logging and mining practices. Education is one way to help drive better policies and practices. We can only hope.

So, in case you needed persuading why springtails really are the best, and as a way to celebrate their incredible beauty, biodiversity and general all round amazingness, here are some fascinating facts about these beautiful animals.

#1. They’re everywhere.

View across Moresby Island, Haida Gwaii, BC. Canada

This photo was taken from the highest point of Moresby Island, on the archipelago of Haida Gwaii, off British Columbia, in Canada. It is, of course, an obvious and blatant way to show off that I’ve been to Haida Gwaii. But, it’s also a photo of many billions of springtails, if you look closely enough. In the soil, in between the rocks, amongst the grass stacks, on the leaves, up the trees, even been blown about against their will in the air, antennae waving feebly. A few hundred years ago, before the logging began, there would have been even more.

They live on the high slopes of Mount Everest, where little else can.

In Antartica, springtails, tardigrades and a flightless midge species are the only invertebrates capable of surviving in such a cold and hostile environment.

The deepest living terrestrial animal is a springtail.

Plutomurus ortobalaganensis was found at a depth of depth of 2,191 metres/7,188 feet in the Krubera-Voronja cave in the Western Caucasus. That’s over a mile or two kilometres directly downwards.

#2. They’re incredibly and ridiculously small.

Megalothorax minimus- 0.5mm big

Mackenziella psochoides male, 0.18mm, Netherlands, © van Bezouw, R.

Part of the reason why so many people have never heard or seen them is because of their size. Imagine making a pin hole in a piece of paper. Many springtails could fall through the hole without touching the sides. Yes, really. That small. Gravity works in a different way for them too.

The smallest fully grown springtail is Mackenziella psocoides, an obscure, moss dwelling animal with the females measuring just under 0.3mm. The males, one shown here, are smaller.

The next smallest are the Megalothorax and Sphaeridia genera. The largest in both genera are around 0.5mm.

Megalothorax incertus juvenile- 0.2mm big

Sphaedia pumilis- 0.6mm big

#3. They’re very brightly coloured.

Uniquely for such a tiny animal, springtails are often highly pigmented. Some are multi-coloured, or ornately patterned, others a single, shockingly bright primary colour. They’re not capable of seeing their colours themselves, having exceedingly primitive eyes. This Katianna species below is the most highly coloured Collembola I have ever recorded.

Katianna species from Tasmania, Australia

Dicyrtomina species from New Zealand

A Lobellinae from Northern Queensland, Australia

An undescribed Pseudachorutes species, New Zealand

#4. Their skin is a meta material

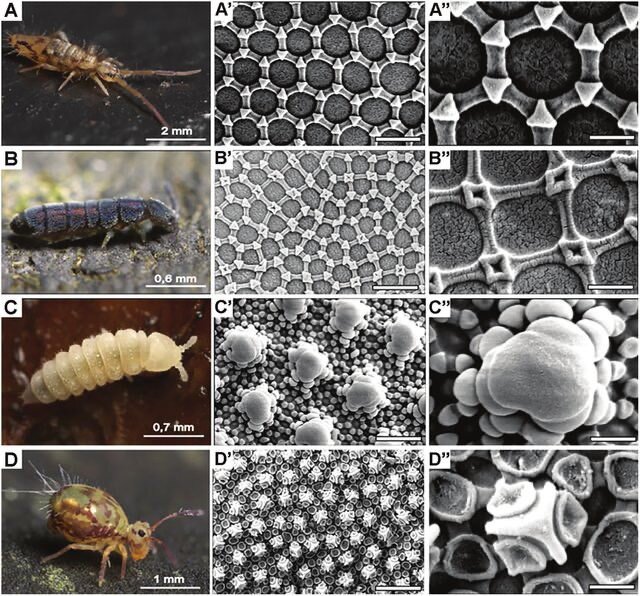

The cuticular tubercles of Sminthurinus niger

Although the above photo is just awful, what it’s showing is not. Each one of those blobs is a micron wide, and form the largest and most obvious part of the complex ‘hierarchical’ cuticular tubercle nanostructures that are behind the springtails’ amazing ability to repel water and dirt. The more complex part of the structures can only be properly observed and understood with an electron microscope. And every genus has a slightly different and distinctive shape, and can be used as another identification tool.

© Bodo D Wilts from It’s not a Bug, it’s a Feature: Functional Materials in Insects

Springtail skin, or cuticle is an omniphobic material, capable of repelling dirt, water, even oil. As such, it’s being studied as a meta material for industry applications. Springtail cuticle has many advantages over other hydrophobic natural materials being studied, like the waxy, water-repelling lotus leaf, or the ability of many aquatic arthropods to trap air between micro setae and respire under water. Its build is unlike anything else in nature, and comes from a probable evolutionary adaption to maintain skin respiration in flooded and over-damp soil environments.

'...they have evolved a non-adhesive surface that exhibits a unique hierarchical structure consisting of microscaled bristles and granules (tertiary and secondary structure) and a comb-like alignment of smaller mushroom-shaped granules with interconnecting ridges (primary structure).' C. Hannig et al 2018

The structures are hierarchical because there are smaller shapes within the larger main tubercles, enhancing these properties. This also appears to enhance the robustness of the skin surface, making it able to resist a certain amount of abrasion, a problem with other structures also capable of resisting water.

The cuticle on a Pseudachorutes species of springtail, magnified through a water droplet

You can see the effect that the cuticle has on water in the photo below of Protaphorura aurantiaca. The cuticle is such an effective repeller of water that the water droplets are almost spherical, enabling them to roll off easily. It’s also very rare to see a dirty springtail as their cuticle repels dust and dirt build up incredibly effectively.

Protaphorura aurantiaca

Pseudachorutes species. Tasmania. As I photographed it, the water rolled off and it was left dry.

Below, in marked contrast, is an oribatid mite- Cepheus dentatus which can’t boast of any water repellent properties at all. Instead, a water droplet sits heavily and half rounded on its back instead of rolling off. It can get worse. Below is another Cepheus dentatus as well as a Hermannia species of oribatid mite. Both are entirely covered in a film of water.

Another reason why springtails are the best.

#5. They’re incredibly heat tolerant.

Not all of them, but a surprising amount are heat tolerant, none the less. Rastriopes is an Australian springtail genus adept at survival in inhospitable dry, high heat. This one lives amongst the the dry stiff grasses of inland Victoria, taking advantage of convective cooling by climbing up the grass stems during the daytime heat, retreating back down to the base during the evening and nighttime. It also has a denser cuticle or skin to help with moisture loss.

Rastriopes sp. Victoria, Australia

I once found Fasciosminthurus quinquefasciatus happily feeding on pollen grains in profusion on agricultural hot black plastic on a farm in Nova Scotia during one of their intense, hot summer days, at a temperature on the plastic of around 50 degrees centigrade. Similarly, I found a Mexican springtail living in between the painfully hot sand grains on a Caribbean beach, and another genus living next to a nearly boiling hot spring in Rotorua, New Zealand. Kneeling to take both photos was extremely painful due to the heat.

Fasciosminthurus quinquefasciatus Nova Scotia, Canada

Neosminthurus species, beach, Quintana Roo, Mexico

Entobryomorpha springtail, Whakarewarewa, thermal spring, Rotorua

#6. They’re cute

A juvenile Temeritas species, Northern Queensland, Australia

I mean- you know. Just look at them. So, so cute. And adorable. And not just some of them. All of them. Every single one.

A juvenile Holacanthella brevispinosa, South Island, New Zealand

Sminthurinus aureus f. ochropus, South Devon, UK

Juvenile Pseudachorutes conspicuatus, North Island, New Zealand

Pseudachorutes species, Northern Queensland, Australia

#7. Some species have a complex dance/courtship ritual.

One of the most famous is the courtship dance of Deuterosminthurus pallipes, seen below, a mainstay on the sunny leaves of early summer bedding plants and bushes in gardens across the UK and parts of mainland Europe. A receptive female and one or more smaller male suitors will engage in a contest of banging heads and fast spinning until one male is hopefully victorious. He then deposits a drop of sperm which the female will take up. Bear in mind that these globular springtails are all 1mm or smaller.

Other species are more acrobatic, like Stenacidia, Sminthurides and Sphaeridia species, who all participate in a ritual where, after some initial manoeuvring and wooing of the prospective female, the male attaches himself to the female’s antennae, using specialised hooks on his antennae. She then lifts him aloft and eventually he can guide her to the spermatophore, a ‘sperm bag on a stick’, attached to the substrate, which she then accepts and absorbs.

An undescribed Sminthurides species’ courtship ritual

Stenacidia violacea courtship ritual

Sminthurides malmgreni courtship ritual

#8. There are actual ‘giant’ springtails

Not all springtails are tiny. The ‘giant’ springtails in parts of Asia, Australia and New Zealand, can be a respectable 13mm big- as large as a small woodlouse. Just to seal the deal, they are also brightly coloured and often with bizarre digitations and tubules. I actually left my job and home behind in the UK specifically so that I could travel to Australia and New Zealand and see them. I didn’t look at a single map, consider the future or have any interest in seeing mountains, landmarks or famous places. I just wanted to see the famous four- Holacanthella, Acanthanura, Wolmersleymeria and Megalanura. And see them I did. And they’re even more beautiful and impressive in reality.

This website, A Chaos of Delight was born from these travels, so I have this lot to thank.

Below is Holacanthella duospinosa, a giant from South Island, New Zealand.

Holacanthella duospinosa

Across Australia there are perhaps up to forty different species, from Tasmania, all the up to Lamington National Park in Queensland, with its sub-tropical rainforest. Very few have been so far described. Tragically, many have probably now been entirely lost due to the fires that swept Australia a few years ago. Apart from one Tasmanian Acanthanura species, giant springtails in both Australia and New Zealand spend most of their time deep within rotten logs in temperate rainforests and old bush.

Above is is the undescribed Lamington giant Acanthanura springtail…

The video below is Wolmersleymeria bicornis, an incredible looking, dragon-like springtail from Tasmania.

Holacanthella spinosa, New Zealand

Acanthanura species, Tasmania

#9. Many species are completely unknown and undescribed

As hinted at in other sections, there are a vast array of undescribed springtails, lying in ethanol tubes in labs around the world as well as a whole load of them completely new to science, hiding in the soil and leaf litter, waiting to be discovered. I’ve actually lost count of how many new ones I’ve found and photographed, but it’s at least forty. When you spend years wandering around obscure rainforests and bush around the world looking at tiny invertebrates, it’s going to happen a lot. It’s always a rather exciting and wonderful feeling, coupled with a little sadness and frustration that there aren’t actually enough taxonomists, interested parties and financial incentives to describe more. Here are a selection, including this one below, that I mention quite a lot- an undescribed Sminthurides species that turned up in the UK, probably originally from Russia, found on my pond and a new UK species. A very old photo hence the bad quality.

Or this Adelphoderia species below from a cave on South Island in New Zealand, which was only supposed to be in Australia.

Or these ones below- a beautiful Temeritas and Pararrhopalites species from the tropics of Australia

Temeritas species

So, to sum up. Springtails really are the best. It’s surely undeniable by now.

Spread the word.